Emission factor matching used to be the slowest, most frustrating part of any PCF calculation. It doesn’t have to be.

Imagine you’re a sustainability manager at a mid-sized supplier. Your customer -a major OEM- just asked for product carbon footprints across your entire portfolio. You pull up your Bill of Material for a single product: 86 components. Seat foams, wiring harnesses, steel brackets, PBT connector housings, PP trim covers.

Now comes the part nobody warns you about.

For every one of those components, you need to find a matching emission factor in a lifecycle assessment database like Ecoinvent — a repository of over 26,000 datasets covering everything from polypropylene granulate production in Europe to carbon black manufacturing globally. You’re not searching for an exact match. You’re searching for the best available proxy, factoring in material type, production process, and geographic relevance.

This is emission factor matching, and it’s the bottleneck hiding inside nearly every product carbon footprint calculation.

Why secondary data matters — and why spend-based shortcuts don’t cut it

In an ideal world, emission factor matching wouldn’t be necessary at all. If every supplier in your value chain provided primary emissions data for their products – actual, measured values from their own operations – you could simply aggregate that data into a precise PCF.

But that’s not the reality today. Most companies don’t have primary data from their suppliers, especially further up the supply chain. Until primary data coverage improves, best practice calls for using secondary data: activity-based emission factors from peer-reviewed LCA databases like Ecoinvent, matched to the specific materials and processes in your BOM. Even with secondary data, this approach already delivers a solid overview of your emission hotspots – which components and materials drive the most impact – so you can prioritize where to source primary data or take reduction measures first.

What you should avoid, however, is relying on spend-based emission factors as a substitute. Spend-based approaches estimate emissions based on how much money you spent in a given product category, using economic input-output models. While they’re quick to calculate and can serve as a rough initial benchmark, they come with serious drawbacks for product-level footprints:

- Inflation distorts results. Spend-based factors are tied to economic models from a specific base year. If prices rise due to inflation, your calculated emissions go up — even if nothing has changed about the actual product or its production.

- Price ≠ impact. Negotiating a better price with a supplier lowers your calculated emissions on paper, while switching to a more expensive but actually lower-carbon material makes your footprint look worse. The signal gets inverted.

- No product-level differentiation. Spend-based factors use broad industry averages. A standard polypropylene component and a recycled-content alternative in the same spend category carry identical emission factors — making it impossible to identify or reward greener choices.

- No actionable hotspot analysis. Because spend-based factors can’t distinguish between materials, production processes, or geographies, they don’t tell you where to intervene. You can only reduce your calculated emissions by spending less.

- Currency and regional complexity. Exchange rate fluctuations and regional price differences add further noise, requiring constant adjustments that many teams don’t have the resources to manage properly.

This is why activity-based matching to LCA databases is the recommended path. And it’s where the matching bottleneck becomes the real challenge.

The hidden cost of manual matching

Traditional LCA work is painstaking by nature. But within the full workflow, one step consistently absorbs a disproportionate share of time and expertise: connecting real-world components to the right entries in environmental databases.

An automotive case study published by Springer illustrates the problem well. Researchers conducting a detailed PCF study for a single vehicle component found that data collection alone took several weeks — with significant effort spent on matching materials to the correct LCA database entries and modeling them in specialist software. Now multiply that by dozens of components across multiple products, and it becomes clear why manual component matching doesn’t scale.

The difficulty isn’t just the volume. It’s the nature of the task itself. Emission factor databases don’t use the same naming conventions as your BOM. Your supplier delivers a part under the trade name “Ultramid A3WG6.” Your BOM lists it as “PA6.6 GF30 connector housing.” Ecoinvent calls the closest match “market for nylon 6-6, glass-filled.” Three names for essentially the same material — and someone has to connect them.

Every one of these decisions requires domain expertise, familiarity with the database structure, and consistent judgment. When different team members make these decisions independently, the same component matched by two different analysts can yield significantly different PCF values – not because either is wrong, but because the process is inherently subjective.

Why this matters now

The pressure to calculate product carbon footprints is intensifying from multiple directions. The EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) now mandates sustainability reporting for the largest companies, and even after scope adjustments through the Omnibus I package, the direction is clear: product-level emissions data is becoming a regulatory expectation. Beyond regulation, OEMs and large buyers are cascading PCF requirements down to their suppliers, often well ahead of any legal deadline.

The challenge is that most companies are trying to meet these demands with manual processes – spreadsheets, expert judgment, and a lot of time. Consulting-led PCF projects often cost thousands of euros per product, with timelines measured in weeks or months. That works for a flagship product. It doesn’t work for a portfolio of dozens or hundreds.

What AI-powered emission factor matching actually looks like

This is where AI fundamentally changes the equation. Rather than having a human expert scan through thousands of database entries for each component, semantic AI matching can process an entire BOM at once — analyzing material descriptions, identifying the most relevant database entries, and ranking suggestions by confidence.

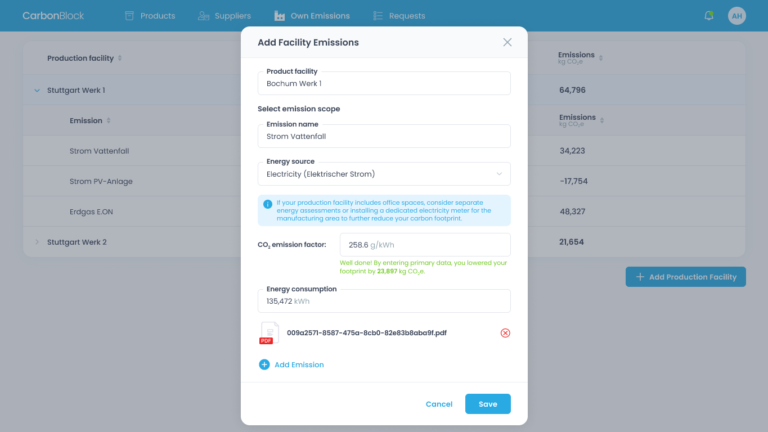

The approach goes well beyond simple keyword matching. The AI extracts component IDs, names, and -if available- descriptions and material data directly from your BOM. It then builds a deeper understanding of each component by combining this BOM data with automated web research, pulling in technical datasheets and specifications to generate a robust semantic description. Based on that enriched profile, the system performs an AI-based similarity search across verified LCA databases and returns ranked dataset matches per component.

Crucially, well-designed AI matching doesn’t replace human judgment. It augments it. Each suggestion comes with a confidence score, allowing the user to evaluate and select the best match. If a match isn’t quite right, additional input -such as a more specific material description or process detail- can be provided to trigger a rematch and improve accuracy. The human stays in the loop – but instead of spending hours searching, they spend minutes reviewing.

From isolated calculations to reusable knowledge

One of the most overlooked inefficiencies in manual PCF work is repetition. A polypropylene bracket appears in three different products. In a manual workflow, that bracket might be matched three separate times, potentially by different people, with different results.

AI-powered tools solve this through component libraries – persistent repositories where confirmed matches are stored and reused across products. Once a component has been matched and verified, that decision carries forward automatically. The hundredth product takes dramatically less time than the first.

This is especially valuable for multilevel BOMs. A wiring harness assembly might include copper conductors, PVC insulation, and tin-plated connectors, each requiring its own emission factor. An AI-powered system can process these nested structures systematically, calculating PCF values that roll up from raw materials through subcomponents to the finished product.

The practical reality: days, not months

The combined effect of AI matching, component reuse, and structured BOM processing is a fundamental compression of timeline. What traditionally took weeks of expert effort can now be accomplished in days.

Upload a BOM, let the AI suggest emission factor matches, review and confirm the suggestions, and generate a complete PCF breakdown — including hotspot analysis showing which components contribute the most to total emissions. For companies managing portfolios across automotive, manufacturing, consumer goods, or fashion, this isn’t a marginal improvement. It’s the difference between PCF calculation being a special project and it being an operational capability.

And as primary data from suppliers becomes more available over time, these tools provide the structured foundation to integrate it — gradually replacing secondary estimates with measured values, component by component, without starting from scratch.

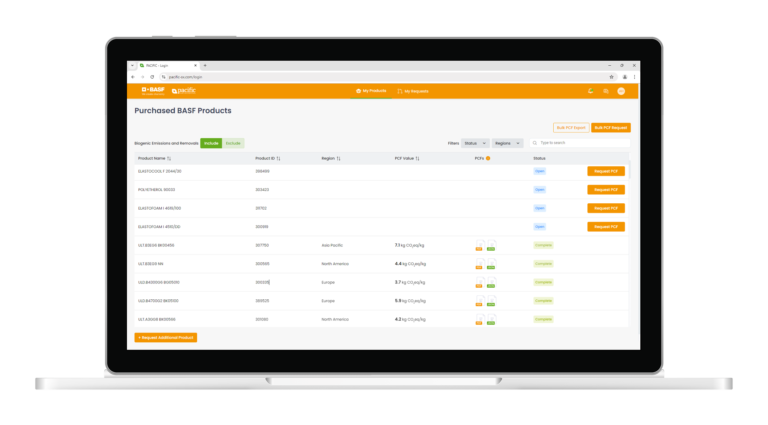

CarbonMatch by CircularTree uses semantic AI matching — developed in collaboration with the German Research Center for Artificial Intelligence (DFKI) — to automate emission factor matching for product carbon footprint calculations. Upload your BOM, match components to verified LCA databases like Ecoinvent, and get audit-ready PCF results in hours, not weeks. Learn more about CarbonMatch →